Dentistry is a hands-on profession. Dental, dental hygiene and therapy students will attest to the hours spent in laboratories, pre-clinical classes and dental clinics honing the psychomotor skills necessary to safely and effectively deliver care to their patients. In addition to exceptional psychomotor skills and a broad foundation of theoretical knowledge, interpersonal and reflective skills are also needed in the education of a skilled clinician. For centuries, the required learning activities have occurred in lecture theatres, seminar rooms and clinics with students and their teachers sharing the same physical space. The rapid disintegration of face-to-face teaching in early 2020 resulting from the CoVID-19 pandemic and associated social distancing mandates has been particularly jarring for a profession whose very essence lies within another’s personal space.

However, it has given those of us working in dental education the opportunity to reflect on how we might reframe dental education in the future by integrating the best that technology offers to support our students in acquiring the attributes necessary to become a competent clinical professional (Machado, Bonan, Perez, & Martelli, 2020).

Late last year, I was afforded the opportunity to lead a curriculum review of the two entry-to-practice degrees – the Bachelor of Oral Health (BOH) and the Doctor of Dental Surgery (DDS) – at the Melbourne Dental School. It has been over 10 years since the current curricula were designed and during that time, not only has technology advanced, but student expectations of their learning environment have also changed. Dental students are expecting that their time at dental school will include online learning, and they see this as helping them transition from a preclinical to a clinical environment (Inquimbert, Tramini, Romieu, & Giraudeau, 2019).

Much of the online learning the Melbourne Dental School students experience was adopted in acute response to the pandemic during 2020, and was not preceded with thoughtful decision-making. To maintain the continuity of dental education, educators scrambled to transition their teaching and learning activities from the traditional physical learning environment to the generally poorly understood, and to many mysterious, virtual environment. As I have been exploring the literature around curriculum, online learning and educational design research, I have been trying to determine how I can piece all these together.

From a pedagogical perspective, as a school we know what direction we should be moving in. We need to reframe how we engage in theoretical dental education to leverage the best from both online and face-to-face class time with a blended learning approach; active collaborative learning, authentic problem solving and opportunities for self-reflection.

The process of designing a new curriculum to meet accreditation standards of a health professions degree, whilst transitioning from a traditional face-to-face, lecture based approach to a blended, collaborative approach is a complex problem (or series of complex problems…) that requires practical solutions. When I first read about the Education Design Research framework (S. McKenney & Reeves, 2020) it seemed appropriate for smaller education design research questions…but to borrow from Kylie Minogue, I can’t get it out of my head.

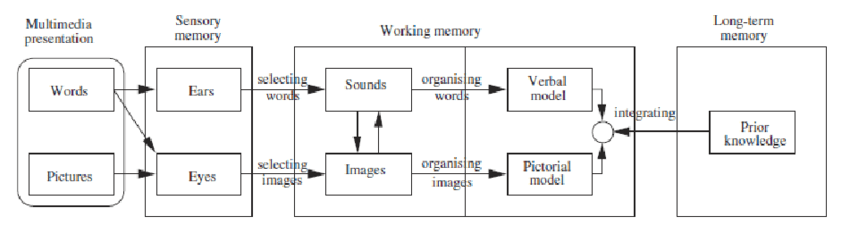

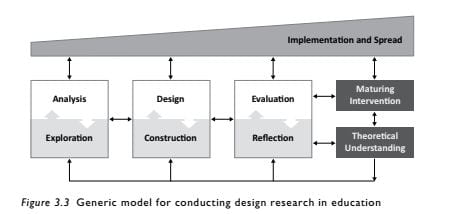

Education design research involves the development of solutions to practical and complex problems. The theoretical knowledge developed during this iterative process can then inform the work of others (S. McKenney & Reeves, 2020). The three main phases of the model for conducting educational design research (analysis, design and evaluation) were based on models for instructional design and curriculum development (S. E. McKenney & Reeves, 2019).

The following video has a description of educational design research.

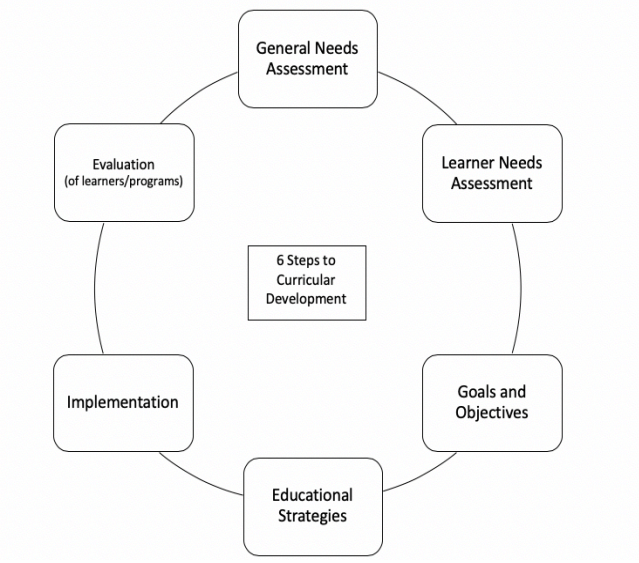

It therefore aligns with the model of curriculum design that I am employing (figure below) (Thomas, Kern, Hughes, & Chen, 2016). The ‘General Needs Assessment’ and ‘Learner Needs Assessment’ steps are ‘Analysis’, ‘Goals and Objectives’ and ‘Educational Strategies’ are ‘Design’ and the ‘Implementation’ and ‘Evaluation’ steps form the ‘Evaluation’ phase of the model for conducting design research in education (above).

However I have questions I need to answer before moving forward. Do I apply an education design research approach to designing a whole 3 (BOH) or 4-year (DDS) curriculum? Or should I be approaching this as multiple smaller research projects? Or should I be doing both? It would seem from the literature that the different steps in the curriculum design process could serve as individual education design research projects, but that they are likely to overlap (Kopcha, Schmidt, & McKenney, 2015). So with my head spinning with questions, possibilities and a little bit of fear I will end with Kylie again…

(Obviously a gif of Kylie’s ‘Spinning Around’ as opposed to just Kylie spinning around was what I was after here…however I could not find one. Also, I doubt it would be considered appropriate to have that much skin on display on a reflective blog on higher education!)

References

Inquimbert, C., Tramini, P., Romieu, O., & Giraudeau, N. (2019). Pedagogical Evaluation of Digital Technology to Enhance Dental Student Learning. Eur J Dent, 13(1), 53-57. doi:10.1055/s-0039-1688526

Kopcha, T. J., Schmidt, M. M., & McKenney, S. (2015). Editorial 31(5): Special issue on educational design research (EDR) in post-secondary learning environments. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(5), i-ix. doi:10.14742/ajet.2903

Machado, R. A., Bonan, P. R. F., Perez, D., & Martelli, J. H. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and the impact on dental education: discussing current and future perspectives. Braz Oral Res, 34, e083. doi:10.1590/1807-3107bor-2020.vol34.0083

McKenney, S., & Reeves, T. C. (2020). Educational design research: Portraying, conducting, and enhancing productive scholarship. Med Educ, 55(1), 82-92. doi:10.1111/medu.14280

McKenney, S. E., & Reeves, T. C. (2019). Conducting educational design research (Second edition. ed.): Routledge.

Thomas, P. A., Kern, D. E., Hughes, M. T., & Chen, B. Y. (2016). Curriculum development for medical education : a six-step approach (Third edition. ed.): Johns Hopkins University Press.