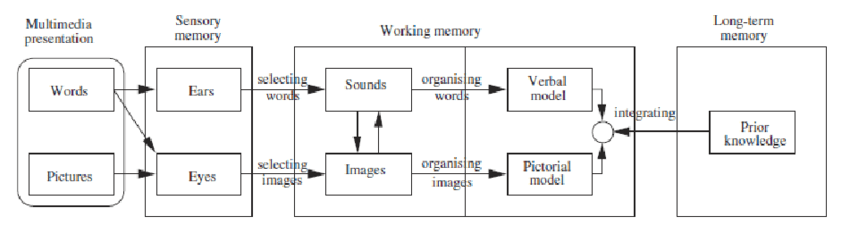

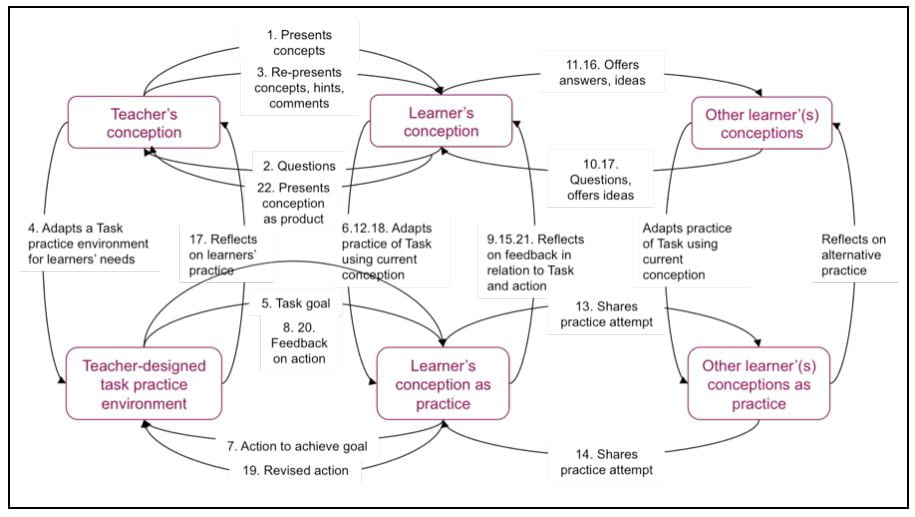

This week I saw Amy Gray and Annabelle Leve speak about a subject they are designing on Global Child Health. During their presentation, they spoke about using the ABC Learning Design Framework, based on Professor Diana Laurillard’s Conversational Framework (Laurillard, 2009). This was not the first time I had come across the Conversational Framework, and I must confess that the figure representing the framework scares me just a little (below).

Figure reproduced from Laurillard, D. (2009). The pedagogical challenges to collaborative technologies. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 4(1), 5-20. doi:10.1007/s11412-008-9056-2

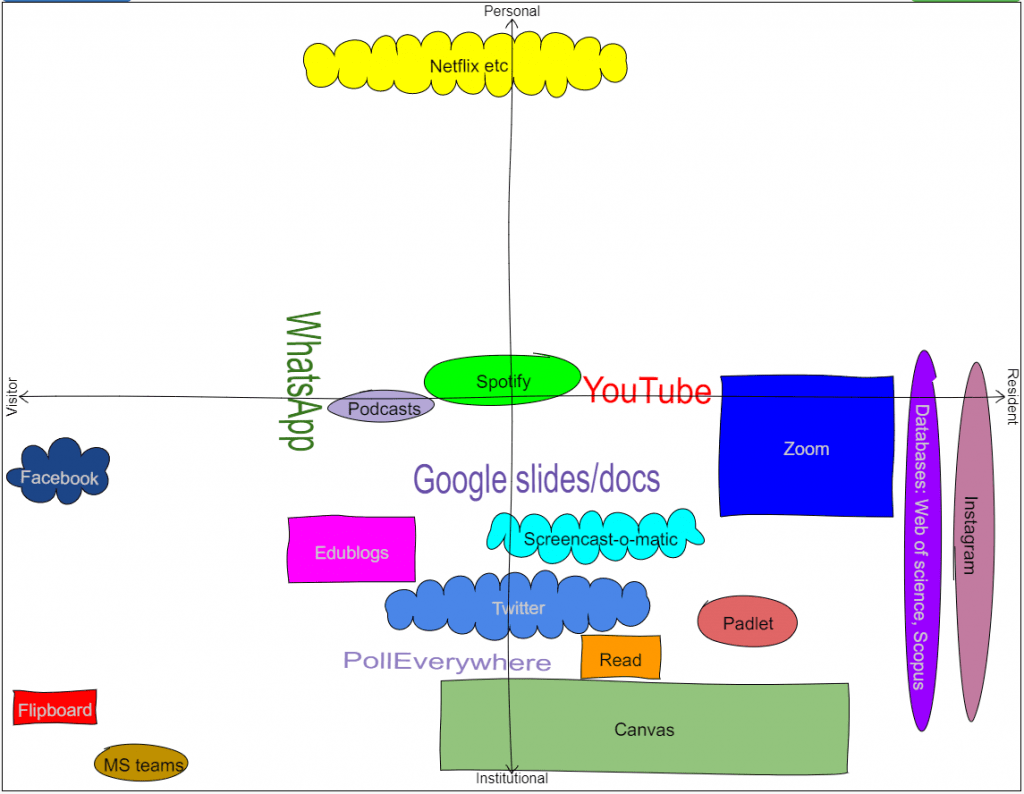

However, one of the things I have learnt over the past few years in exploring more about learning and education theory is that to overcome the feeling of being a ‘visitor’ in this literature, I need to recognise this feeling and take the time to explore these theories and frameworks to the point that they become familiar. To borrow from David White and Alison Le Cornu’s typology of ‘Visitors and Residents’ for describing the use of technology, I want to feel like a ‘resident’ in this field of learning and teaching theory (White & Le Cornu, 2011).

So these last few days, that is what I have tried to do with Laurillard’s Conversational Framework. In addition to reading, one of the most helpful resources I found was this video of Diana Laurillard herself describing the framework and (reassuringly) acknowledging its necessary complicatedness.

The framework is based theories of how students learn, and represents the actions of both teachers and students in the learning process. It can provide those designing learning activities with a guide to the types of learning students will be engaging in and is particularly relevant to helping appropriately employ technology in this process.

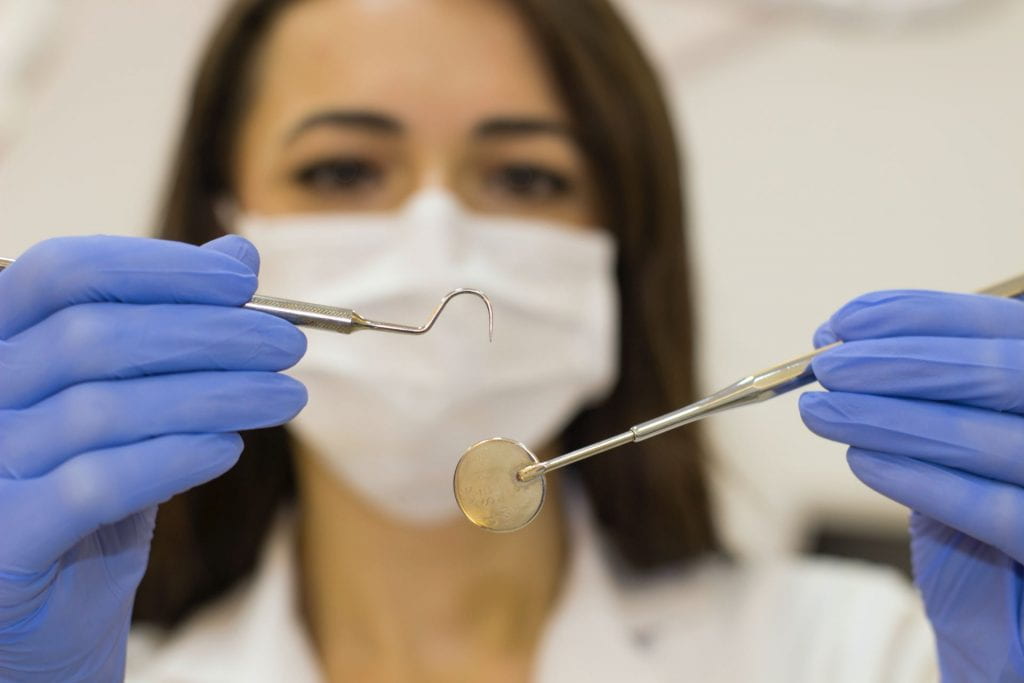

Now to jump to dental education…

Teaching academics at Dental Schools generally hold their role due to their expertise, experience and research contribution to a field such as periodontics, dental materials, epidemiology, oral medicine, health promotion…

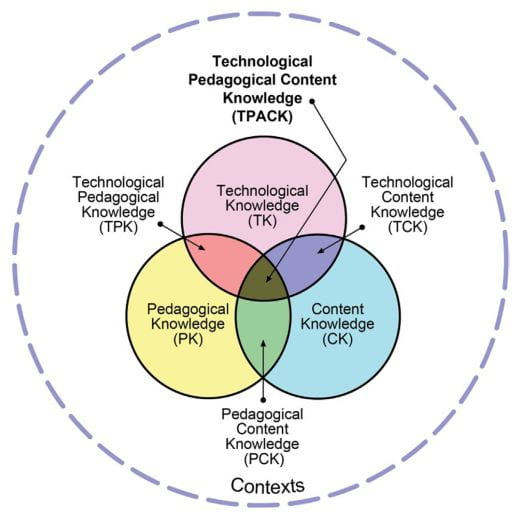

However, to teach, this content expertise or knowledge is only part of what is required. Pedagogical and technological knowledge are also required. I have found the TPACK framework useful for conceptualizing this, as it distinguishes between the triad of content knowledge, pedagogical knowledge and technological knowledge (Mishra & Koehler 2006) necessary, particularly when teaching online. Teaching online requires due diligence being paid to the interface between sound pedagogical knowledge and technological knowledge and in neglecting this, potentially fails to best serve our students and profession.

Figure reproduced from (Mishra & Koehler, 2006) via (Roddy et al., 2017).

Those of us tasked with the responsibility of reviewing the MDS curricula, and reforming the assessment and feedback strategy at the School, are aware that the success of what we are doing will depend upon working with colleagues to collectively develop the technological and pedagogical knowledge as we embrace a blended learning approach to dental education, and exploit the online learning environment for the benefit of our students. I have written a little bit about this in a previous post.

Last night, while reading about the Conversational Framework, serendipitously, a colleague posted the following tweet:

It was her point of “Now we need to teach the teachers how to teach online” that brought these two frameworks together for me, and the previously hazy pieces of the puzzle started to become clearer, and fall into place. One of our main challenges, particularly in employing online learning in theoretical dental education is to move away from students engaging in ‘acquisition’ and have them spending more time on other types of learning; inquiry, discussion, practice, collaboration and production while online.

I think we can employ the Conversational Framework to help support the development of pedagogical and technological knowledge in our School as we work to design the learning activities as part of implementation of our new curricula.

To do this, we could use ABC Learning Design framework and learning designer toolkit which are based on the Conversational Framework. This provides a practical framework which will help staff to focus on the actions of the student when designing learning activities. This could support staff to take a student-centered approach to designing learning, and move away from the more traditional passive didactic approach which has been the basis of theoretical dental education for many decades.

The idea is in its early stages, but I think I can feel it coming together…

References:

Laurillard, D. (2009). The pedagogical challenges to collaborative technologies. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 4(1), 5-20. doi:10.1007/s11412-008-9056-2

Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge(6), 1017. Retrieved from https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=sso&db=edsbl&AN=RN188285593&site=eds-live&scope=site&custid=s2775460

Roddy, C., Amiet, D. L., Chung, J., Holt, C., Shaw, L., McKenzie, S., . . . Mundy, M. E. (2017). Applying Best Practice Online Learning, Teaching, and Support to Intensive Online Environments: An Integrative Review. Frontiers in Education, 2. doi:10.3389/feduc.2017.00059

White, D., S., & Le Cornu, A. (2011). Visitors and Residents: A new typology for online engagement. First Monday, 16(9). doi:10.5210/fm.v16i9.3171